Eubie Blake composed the Baltimore Todolo in 1910.

I spent over 40 hours painstakingly transcribing this ragtime classic into LilyPond source code, without having viewed or referenced any other existing transcription. The idea was to generate sheet music that accurately represents the music exactly as played, as opposed to someone’s own approximate version of it. It’s gratifying to be able to play it just like Blake, complete with most of the proper timing and dynamics. It gives insight into the thought process and piano technique that makes his style unique, even clarifying some of the finger and hand motions he must have used.

When transcribing, it’s often difficult deciphering which notes are being played, especially in chords during noisy sections of music. This kind of transcription would not be possible without software like “Transcribe!” which performs a frequency analysis and allows the music to be played at speeds ranging from normal to very slow, without frequency shift – but also allows a frequency shift when it’s useful to better hear lower or higher notes. I often end up repeating a single chord for minutes on end while trying to reproduce the notes on my nearby piano keyboard until the right combination suddenly clicks in an “aha” moment.

In some cases it might appear a composer playing his own composition has made a “mistake.” However, one could reasonably argue that that’s not possible, especially since he never plays it the same way twice. For this reason I reproduce most of the oddities in the recording. Some of them include measure 8 (G+A), 56 (B-flat strike indicates probably played RH only), 67 (final F octave slid onto G), 82 (played even weirder than this), 84 (pounding almost indecipherable), 90 (the 2nd high D is played nearly as C, tied with the following C), 93 (he slides the 4th finger many times in Charleston Rag), 94 (odd RH), 96 (missing D-flat in LH).

Blake is often heard shouting phrases during live performances. Those are included for fun; I think I’ve got them right.

Like much ragtime music, this piece is to be “swung,” meaning that pairs of 8th notes are to be played more like triplet 8th notes, where an 8th rest is added in the middle of each pair. I note this at the beginning of the piece, then present the whole piece using plain 8th notes. I also have LilyPond add swing during MIDI generation. This method of writing swung music using plain 8ths is much preferable to what some transcribers do, which is to use a dotted 8th and a 16th. Besides resulting in a messy score, the rhythm is just wrong. The overly-pronounced swing irretrievably ruins the MIDI output. In this piece, the magnitude of the swing varies from considerable to barely detectable. I’ve tried to notate that using an asterisk for straight 8ths. There isn’t any standardized notation for that, other than by writing out the words straight eighths, which is overkill when just a few notes need to be straight, and frequently so.

The source recording I used was released by Columbia Records in 1969 and was made available on YouTube. I could only find this one version, unlike the Charleston Rag, which has a piano roll and at least three recorded performances by Blake himself. In the case of the Charleston Rag, my transcription is mostly accurate to a recording in 1972, but I also incorporated some details from an early piano roll that found more enjoyable to play.

Here is a cover page I designed using GIMP (the open source GNU image editor similar to Photoshop).

And here is a PDF of my transcription (4 pages):

Here is a MIDI file for download, and also an on-line MIDI player for instant gratification. This barebones MIDI player doesn’t do it justice, so I’d recommend downloading the MIDI and playing through a better program. LilyPond’s MIDI output is pretty good when using the “articulate” module. I also use a module that generates the swing (swing.scm), which I’ve further customized to exclude the small sections that are to be rendered as straight eighths.

The Charleston Rag originally went by other names such as “Sounds of Africa”. Eubie Blake composed this in 1899 while in his early teens. It didn’t get written down until as late as 1917 when it was also made into piano rolls.

Terry Waldo, a student of Eubie Blake, wrote a transcription in 1972 when Blake was in his 90s. Other publicly available sheet music is not of very high quality, so I determined to edit and typeset a version here. I referenced several sources for this:

First, a sheet music cover image that I created using Bing Generative AI (DALLE-3) and the GIMP image editing tool:

Here is the transcription (6 pages):

Here is the MIDI player and download:

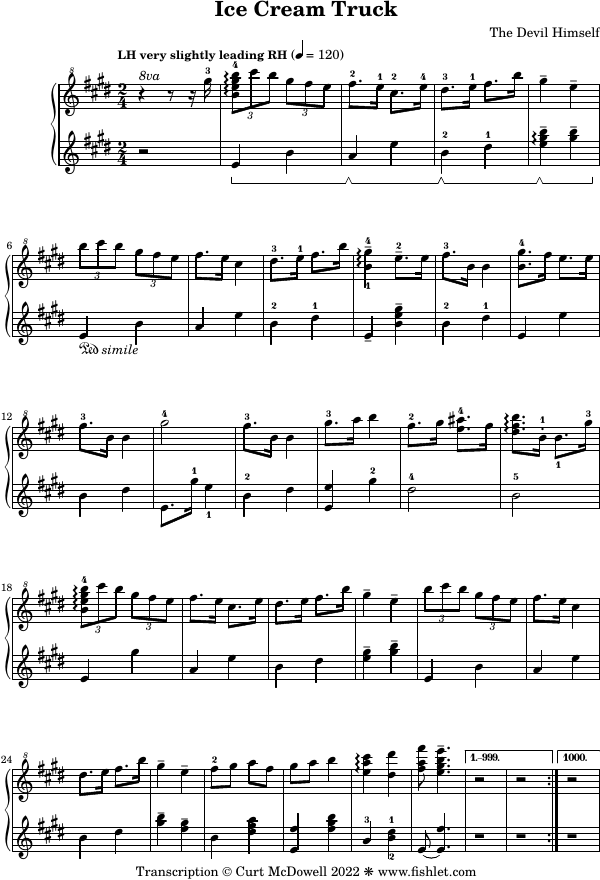

My neighborhood in California is plagued by an ice cream truck that can be heard often from blocks away. Sorry if you have been subject to it. If so, you might want to skip this to avoid psychological trauma.

The usual software was used to transcribe (Transcribe!) and typeset (Lilypond) this music. Unfortunately, the MIDI generator in Lilypond does not arpeggiate arpeggios.

If you have not yet seen the original post about my Merry Go transcription for player piano, please read about it here.

The transcription was initially organized in four voices in the Lilypond source file. This made it relatively easy to direct Lilypond to write out a couple extra scores for a single-piano duet version. The two treble voices can be played by Primo, and the two bass voices by Secondo. This shows the power of Lilypond for maintaining multiple renditions from a single source file.

The duet was still not immediately playable. A few chords had too many notes and needed minor tweaks. The last 3 measures needed an alternate playable version; I think I struck a reasonable compromise by having the players alternate the fast final runs, and by reducing the 3-octave run to 2-octave. And in this version, the final chord does not contain all eight C keys on the piano!

As of this writing, the duet has not been performed by two people. I did record myself playing Secondo and then played Primo over it, but there may remain some awkward overlaps with two players on one piano.

If you’d like to print the 6-page duet in book form, I would recommend printing page 4 as simplex, pages 1 and 5 as duplex, pages 2 and 6 as duplex, and page 3 as simplex. Then you’ll be able to have Secondo on the left facing Primo on the right, for 3 pairs of pages. The page numbering is designed with this scheme in mind.

In 2013, I learned to play the Sousa/Horowitz piano transcription as best as I could. I found three sheet music transcriptions (Pellisorius Editions by Jon Skinner; Christian Jensen, 1999; Florian Wolf, 2010). Each edition differed from each other, and also differed from the available audio recordings in minor but unsatisfying ways.

I took it upon myself to create a new, highly accurate transcription of one particular performance by Horowitz: the seminal April 23, 1951 radio broadcast from Carnegie Hall. I attempted to capture as much detail as possible all aspects including notes, dynamics, pedaling, and tempi. I even tried to capture his apparent mistakes, which I have largely indicated in the music. (Of course, this being his own version, “mistakes” is a very subjective term.)

Once again, I relied on Transcribe! software for listening and GNU LilyPond for typesetting. The process took many days.

The PDF file of the sheet music:

The MIDI file generated by LilyPond. I didn’t put much effort into this so the dynamics leave a lot to be desired. Generating a MIDI file was not an objective.

My amateur performance on YouTube:

The original recording I started with was from the video below. A fourth sheet music transcription that is displayed matched to the music doesn’t correspond well.

A couple other notable professional and amateur performances:

If you’ve watched enough compilation videos on YouTube, it is likely you’ve heard Merry Go, a fast-paced, 2-minute ragtime-ish piano song published by Kevin MacLeod in 2010. It is one work out of a large body of high quality digital music that Kevin shares under the Creative Commons By 3.0 license, for anyone to use for any purpose, royalty-free. Not surprisingly, his music has become some of the most-used background filler on YouTube.

Here is a video of the audio of Merry Go by itself (because people upload stuff like that).

Depending on your mood and temperament, Merry Go can be either energizing or irritating. Because of the latter, someone had to do it: here is a video of the song playing for 10 hours. There is also a 1-hour version, a slowed-down version, MIDI transcriptions, and others.

Watching a useless video late one night, this song played, and it piqued my interest. Its use of sforzandos and staccatissimo is striking. It’s fast, but sounds simple enough. I decided to attempt a sheet music transcription. However, I quickly found out that the apparent simplicity belies a greater complexity than one would expect. There are a lot of notes! It got even more interesting as I discovered its origin..

A reproduction aiming for fidelity to the original would be most suitable for performance by MIDI and/or player piano. It is impossible to play on solo piano.

Using the Transcribe! software, I listened to Merry Go for hours in excruciating detail, at different speeds and octave shifts, in order to generate a transcription. To test for the presence of specific notes, I would listen carefully while hitting them on a keyboard while simultaneously looping short snippets of the audio, often just individual chords. There are several things that limit how accurately the notes can be divined. Some chords contain upwards of 10 simultaneous tones. Very quiet or low tones may get drowned-out. Artifacts of digital encoding and frequency scaling through re-sampling filters result in ghostly sonorities and sympathetic octave blurring. It took four or five passes/editions before I was satisfied I hadn’t missed too much. Nevertheless I’m sure Mr. MacLeod would cringe.

Having written out the initial transcription on music staff paper, I then coded it as a text file in the GNU LilyPond music description format. LilyPond is an amazing piece of software that reads a description and generates beautiful typeset sheet music in PDF format, as well as generating MIDI output. There is a big learning curve, however. I’m sure it comes a lot more naturally to people who are already experienced computer programmers. But if you are a geek who needs to typeset music, you need LilyPond!

Here is the resulting MIDI output. Dynamics processing by LilyPond is somewhat rudimentary and leaves something to be desired. As with everything else in LilyPond, perfection is possible given enough time (worst case, it’s open source!)

You can play the MIDI file in your browser using the tools from www.midijs.net, but it doesn’t sound as good as native players.

And of course the PDF sheet music.

Finally, for the curious, or those who might want to tweak further, the LilyPond source file, under the same license.

Please have a Merry time with it and comment below.

UPDATE! Read about the duet version!